"ELIZA-- a Computer Program for the Study of Natural Language Communication Between Man and Machine"

-

In the 1960s Joseph Weizenbaum created “ELIZA,” a program which mimicked a psychotherapist, generating conversations such as:

User: Men are all alike.

ELIZA: IN WHAT WAY

User: They’re always bugging us about something or other.

ELIZA: CAN YOU THINK OF AN EXAMPLE

User: Well, my boyfriend made me come here.

ELIZA: YOUR BOYFRIEND MADE YOU COME HERE

User: He says I’m depressed much of the time.

ELIZA: I AM SORRY TO HEAR YOU ARE DEPRESSED.Weizenbaum’s program used a limited number of schemas to frame discourse around the norms of psychiatric conversation. ELIZA generated responses to user input by first, decomposing a sentence into its keywords, second, matching those keywords with a template, and third, applying the associated language transformation, from “I” to “you:” for example, “my boyfriend made me come here,” would become “Your boyfriend made you come here.” ELIZA illustrated that simple responses, even ones that seem to simply use repetition to show the computer is ‘listening,’ can prompt a conversation that can feel emotionally satisfying for a user. Computer scientist Robert Abelson argued that forgetfulness can feel more human than precise response, such as when readers of novels don’t remember all the details of a plot but rather its general arc. Abelson suggested that in fact “people’s skill in forgetting things, particularly over the long run, might provide a good model for AI.”

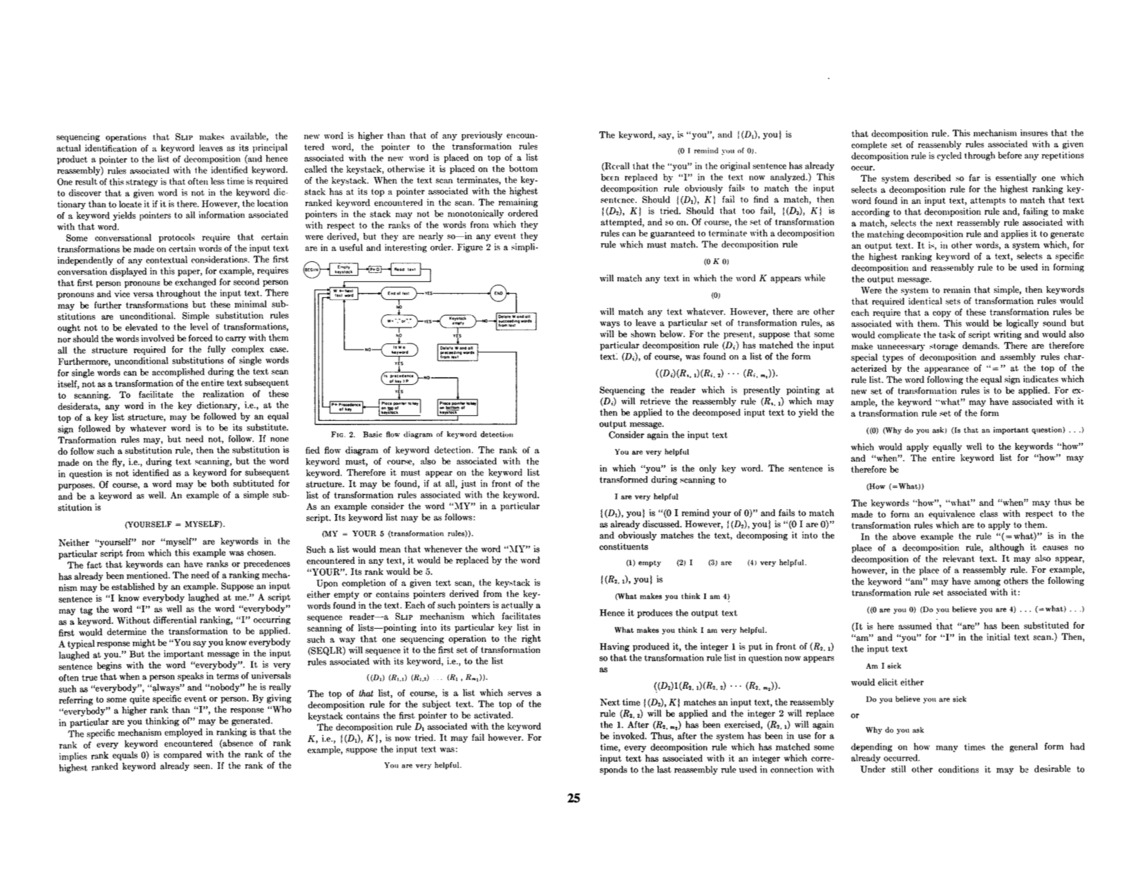

Though ELIZA did not encapsulate a deep model of human conversation, it provided surprisingly powerful results. And yet, following his invention Weizenbaum became more skeptical about AI; he cautioned that we shouldn’t confuse functional success with a deep model of intelligence; ELIZA might approximate a conversation between therapist and patient, but not capture how psychiatrists understand the experience of love. In the journal article page displayed here, you can see a diagram of ELIZA’S keyword detection process, whereby ELIZA ranked certain words which would then be subjected to “decomposition rules,” or transformations such as from “I” to “you.”

Introduction

- Label

- "ELIZA-- a Computer Program for the Study of Natural Language Communication Between Man and Machine"

- Author

- Joseph Weizenbaum

- Original Publication Date

- 1966

- New Publication Date

- 1966

- Publisher

- Communications of the ACM

- Location

- Butler Stacks

- Case

- 7