"The Metanovel: Writing Stories by Computer"

-

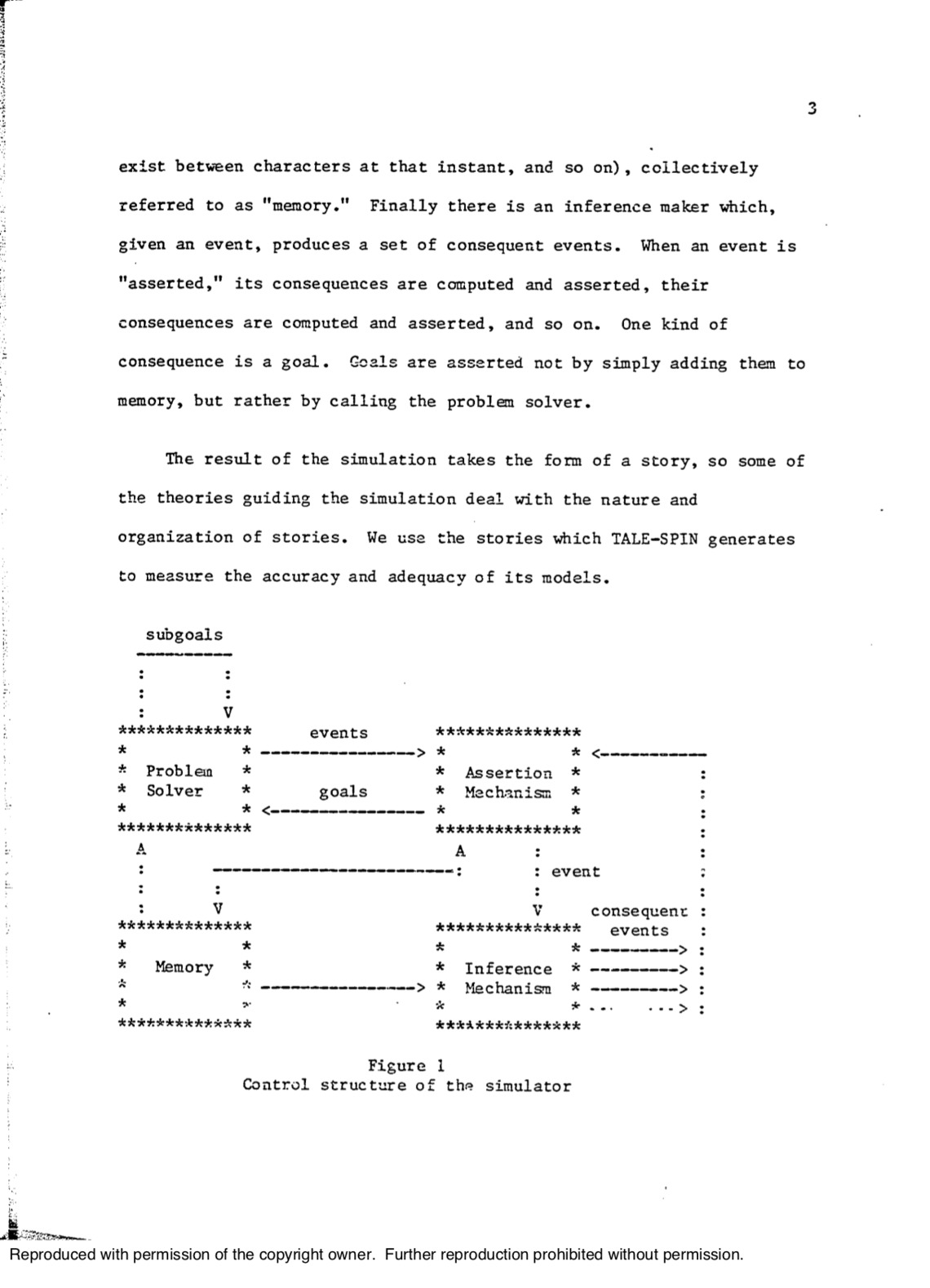

James Meehan’s TALE-SPIN (1976), supported by the Advanced Research Projects Agency of the Department of Defense, used a nested, schema-oriented approach. The program worked by prompting a reader to select from a list of predefined characters— a bee, bear, girl, fox, etc. The character schema would be instantiated using randomly-chosen attributes (e.g. tall, black bear living in a mountain cave). The program would then generate templates for character states of mind and motivations (e.g. bear is hungry and bear does not know where to find food). Next, the program initiated its three major templating components— a Problem Solver, an Assertion Mechanism, and an Inference Mechanism— alongside a Memory Component (see the diagram displayed here). The Assertion Mechanism exchanged information with the Problem Solver to create events (e.g. Mr. Bear works together with his friend bee to procure honey; They walk across a meadow towards a beehive; Bear climbs tree), and the Inference Mechanism aligned these events into a cohesive sequence culminating in a resolution (Mr. Bear is no longer hungry); at this point the program triggered its next action through the same sequence. Although TALE-SPIN may seem less context-specific than ELIZA or “Baseball,” the diagram displayed shows that its tales used a particular model of story-telling—a structure that by no means encapsulates all story types.

Introduction

- Label

- "The Metanovel: Writing Stories by Computer"

- Author

- James Meehan

- Original Publication Date

- 1976

- New Publication Date

- 1976

- Publisher

- Yale University, Department of Computer Science

- Case

- 7